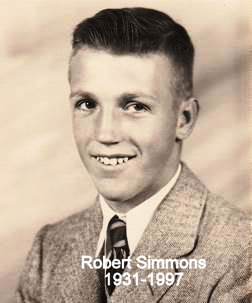

My father had been a troubled man. As a nineteen year old Marine in Korea, he had participated in the landing at Inchon, and the breakout and retreat from the “Frozen Chosin” reservoir. He was deeply scarred by these experiences, and very seldom mentioned what he had experienced there.

Although he worked with the VA to find relief for what we now call post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD), he found no relief. In the end, alcohol was his cushion and crutch. Alcoholism is a terrible burden, both to the alcoholic and to everyone in their life. I was shocked and saddened to hear of his passing, but I also felt relief that his struggles were now over. I was relieved for myself that there would be no more worrying about getting a “There’s been an auto accident” phone call in the middle of the night.

My father and I were close and had much in common. I was the oldest child, and had followed him into the same pipefitters trade. Indeed, we had worked together on the same construction projects for several years. It was never easy, but I was able to know my father in ways that no one else in my family was able to. I believe that his passing affected me as much as anyone. I recall that the day we learned of his death, I was emotionally fraught and tender all day, even though I didn’t get the news until later in the day. How can you ever really be prepared to lose a parent?

About two weeks later, I had an unusually vivid dream. I dreamed that I was looking into my father’s face. No words were spoken, but I was struck by his amazingly bright hazel and clear eyes. His eyes were so clear and bright with optimism and peace in a way that I had never seen before.

I have found great relief and comfort in the experience of his ability to see with beautifully clear eyes. I consider it to be a divine gift which has stayed with me for many years.

—Joel B. Simmons